Prof Dov Stekel, University of Nottingham

Depression among young adults (aged 18 to 29) is becoming more common around the world, especially during the challenging years of becoming independent, finding work, and navigating adult responsibilities. Our recent article, published in Lancet Psychiatry, looked at all the research we could find on what factors across different parts of life, such as health, family, money, community, or environment, might protect against depression. We systematically reviewed 139 studies, covering over 17,000 young people.

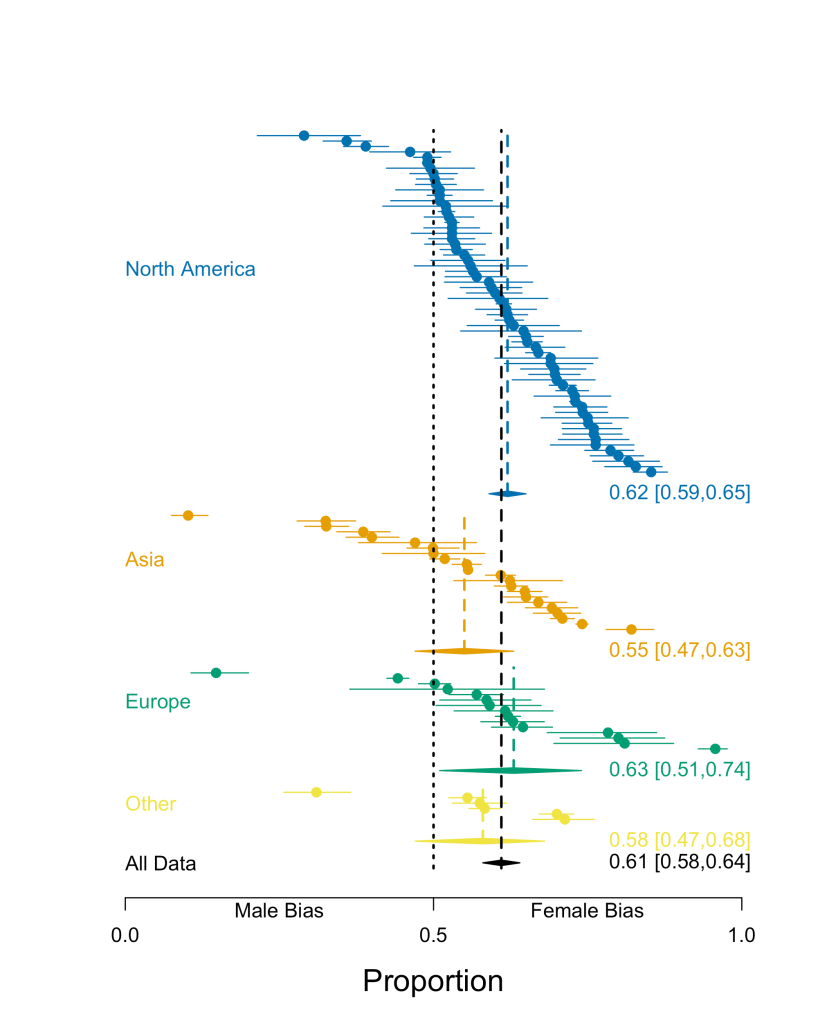

I created the graphs and visuals for this article. My favourite one is a type of chart called a Forest Plot, though The Lancet didn’t include it in the main article (it was moved to the supplementary section, which people don’t always look at). That’s a pity, because the Forest Plot makes an important point: the studies we looked at are so different from one another, especially in terms of the gender of participants and where the studies were carried out, that it is not actually possible to combine their findings into a meaningful summary. This type of summary is known as a meta-analysis, and in this case, the data just isn’t consistent enough to allow one.

Still, the Forest Plot shows something important.

While we can’t combine all the studies into one conclusion, we can see a clear pattern: most of the research on young people’s resilience to depression is focused on girls or young women, and most of it takes place in North America — especially among university students. We even tested this statistically, and it holds up.

That means we know quite a lot about how mental health and resilience work for young American and Canadian women in college/university, but far less about other groups such as young men, or any other group outside of the US and Canada. Crucially, we know almost nothing about young people in African countries, which is especially important since the R-NEET project is based in South Africa and Nigeria, and because by 2050 the youth population in Africa will be bigger than anywhere else.

This kind of imbalance in research matters. If we want to understand mental health globally, and build support systems that work for everyone, we need to change how, where, and with whom studies are done. It’s something those of us in academia (and our funders) need to take seriously, and work to fix.

As well as this important finding, we also learned that the most commonly reported protective factors were personal traits (like positive thinking and psychological resilience) and social support (especially from family or friends). But very few studies looked at how things like poverty, institutions, culture, or the physical environment affect mental health, or how different systems interact to shape resilience.

That’s also a problem. If most studies only look at individual or family-level factors, we miss the bigger picture, and risk misunderstanding what young people in particular contexts need to manage depression. To support young people globally, we urgently need more diverse research that recognises the complex web of systems that shape mental health, especially in the parts of the world where most young people actually live. R-NEET is taking a big leap in the right direction, and I hope this article will be a call to others to fund and deliver research that speaks to this agenda.